Written by Yehuda Smirnov, Hoshea Yarden, Hai Vaknin and Noam Pomerantz

- TL;DR

- Introduction

- Pointer‑Only LoadLibrary Injection

- Investigating Remote-Thread Creation Noise with ETW

- CreateRemoteThread + SetThreadContext Injection

- NtCreateThread Context Injection

- RedirectThread Tool

- Injection Detection Logic Theory

- Research Notes

- A Note on “GhostWriting” and Related Work

- Conclusion

TL;DR

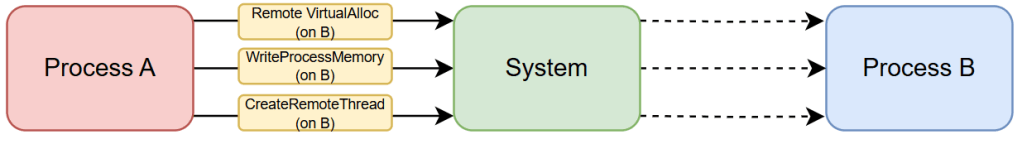

Most process injection techniques follow a familiar pattern:

allocate → write → execute.

In this research, we ask: what if we skip allocation and writing entirely?

By focusing on execution-only primitives, we found distinct approaches to inject code without allocating / writing memory:

- Inject a DLL using only

CreateRemoteThread. - Call arbitrary WinAPI functions with parameters using

SetThreadContext. - Utilize

NtCreateThreadto remotely allocate, write and execute shellcode. - Expand the technique to APC functions such as

QueueUserAPC.

Find the RedirectThread Github repo here

Introduction

Modern Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) stacks typically watch for three signs of classic process‑injection:

- Allocation of fresh memory (

VirtualAlloc[Ex]) - Modification of that memory (

WriteProcessMemory,VirtualProtect) - Execution to it (

CreateRemoteThread, APCs, etc.).

Our goal in this research was to test the lower bound: can we trigger only the execution primitive, skipping both allocation and write primitives, yet still land malicious code in the target?

The idea started with a rumor that huge memory pages are always allocated and mapped as read–write–execute (RWX), even not specifically requesting these.

Post Research Note: when we tested this, it wasn’t the case.

This raised a natural question:

Would security tools treat this differently from a typical RWX allocation?

If so, skipping the allocation part of the chain could bypass part of the usual detection logic. And if that’s possible, what about skipping the data injection step too? If the bytes we need already live inside the target, we might not actually have to write anything new at all.

This sparked an idea:

If we already have valid, addressable data inside the target process, could we take the classic DLL injection – the LoadLibrary method, and simply point it at existing data within the target process, then let Windows do the rest?

Why LoadLibrary?

LoadLibraryA/W automatically appends “.dll” to whatever string pointer it receives and then resolves the usual DLL search order (stackoverflow.com). With that behavior we can find an existing in‑process string (e.g. “0“) and drop a file named (for example) 0.dll somewhere earlier in the search path.

This would launch a remote thread whose start routine is LoadLibraryA, with its argument set to a character pointer (e.g., “0“), finally causing the DLL to be loaded into the target process.

But how are we going to find this existing in-process string?

Shared Memory 101

When Windows maps file‑backed sections (e.g., ntdll.dll) into multiple user‑mode processes, the sections are backed by the same physical memory; each process merely receives its own virtual‑address view.

Copy-On-Write protects shared memory regions until a process attempts to modify them. At that point, the kernel creates a private copy of the page to ensure the process does not alter memory that’s shared across all processes in the system.

Since Windows Vista, ASLR randomizes base addresses every startup. System DLLs are loaded at a consistent base address across all processes to optimize relocation performance.

As a result, an offset like ntdll + 0x4 should point to the same bytes in all processes.

Then we can locate a pointer to a character locally and reuse the address when calling LoadLibraryA in the target process.

Many convenient string literals live in ntdll.dll which is loaded by all processes. We chose to use “0” for our case.

Pointer‑Only LoadLibrary Injection

The Proof‑of‑Concept below demonstrates the minimal steps required to turn that idea into a working process‑injection primitive.

- Locate an in‑process string

- Search

ntdll.dllfor a static ASCII string such as “0” (0x30 0x00). Because the DLL is mapped at the same offset in both the target process and our own process, the virtual address should be valid across both processes.

- Search

- Prepare the payload DLL

- Build

0.dllwith implant of choice. - Drop the DLL into a directory that resolves via search order.

- Build

We are not necessarily limited to classic search‑order hijacking. Perhaps it is possible to abuse

DefineDosDeviceWor NT symbolic links to load the payload from arbitrary locations such as SMB shares or WebDAV mounts.

- Create the remote thread

- Note that the address of

LoadLibraryAis obtained from our own process, similar to the method in step 1.

HANDLE hThread = CreateRemoteThread(

hProcess,

NULL, // default security

0, // default stack size

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("kernel32"), "LoadLibraryA"),

(LPVOID)0x7FFE0300, // pointer to shared NUL byte inside ntdll

0, // run immediately

NULL);

- Execution

LoadLibraryAappends “.dll”, resolves the path, and loads0.dllinto the target process:

We got an unexpected but exciting result:

- By skipping memory allocation and writing, a well-known injection technique has bypassed detection in two industry leading EDRs.

- We also tested the regular DLL injection technique (which involves writing memory), and it was detected by both EDRs.

- This small tweak revealed that many techniques rely on the same early-stage behavior and how easily that behavior can be avoided.

This led us to rethink the injection chain:

- Most techniques follow the same pattern: inject data → trigger execution.

- Across many of them, the execution trigger is the common piece.

So we asked:

- Do we really need to inject data at all?

- What if we just focused on the execution trigger?

Instead of swapping out each part of the chain, we doubled down on the trigger and pushed to see how far we could go with just that.

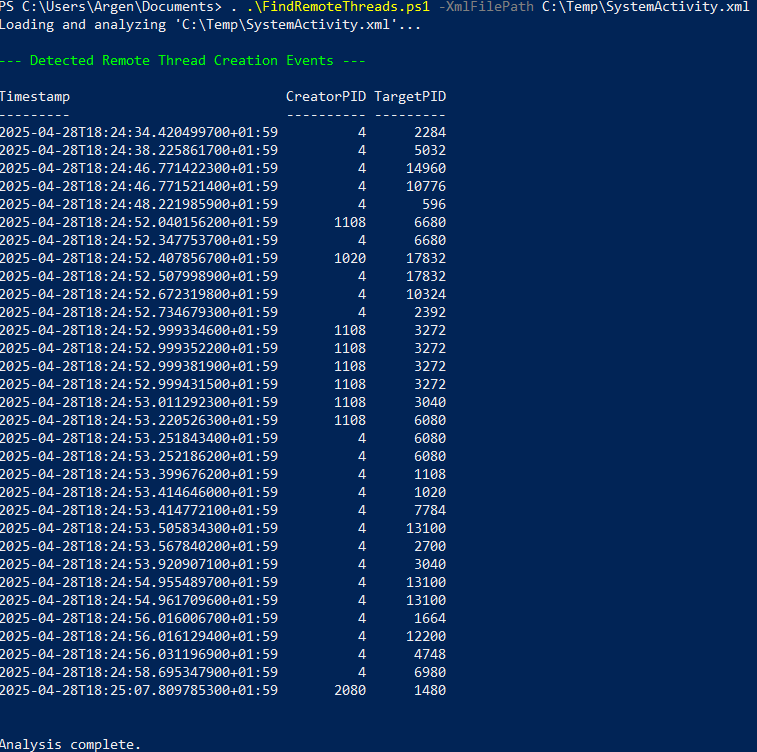

Investigating Remote-Thread Creation Noise with ETW

Before diving deeper, we took a quick detour prompted by a simple question:

Is this just a detection oversight?

Why don’t security products flag any remote thread creation as malicious? Isn’t it rare enough to catch with a simple whitelist?

Turns out — not at all. Remote thread creation is surprisingly common and is used by:

- Application resource monitors

- Performance profilers

- Instrumentation and tracing tools

- Debuggers, compatibility shims, accessibility helpers

- Enterprise agents and endpoint frameworks

To measure the baseline “noise”, we wrote a small ETW-based tracer to capture and correlate thread creation events where the creator PID ≠ target PID. ETW gave us all the data we needed.

Looking through the data captured of less than a minute on a clean Windows install, we already find some thread creation across different processes:

At this point, we already felt it was worth digging deeper into the execution trigger, while avoiding allocation and modification.

If EDRs don’t flag malicious activity based on the execution step alone, even when using the infamous CreateRemoteThread, then the question becomes: how powerful is this primitive, and where can we take it next?

CreateRemoteThread + SetThreadContext Injection

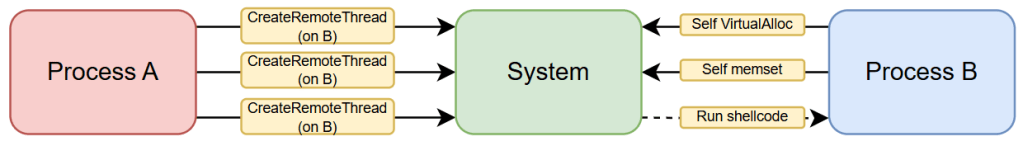

Our first thought on leveraging CreateRemoteThread further was to avoid dropping a DLL to disk and attempt to implement a memory only injection with it. We aimed to achieve a similar power to the classic remote Allocate → Modify → Execute chain.

The obvious question is: why not just call those functions directly inside the remote process?

If the new thread we create inside the target process is designed to allocate and modify memory within its own process, then we can simply take the existing techniques for remote memory allocation/modification and adapt them into ‘self’-allocation/self-modification methods.

Even better, we can use any local functionality already available in the target process for our primitives — instead of being restricted to just WinAPI or syscalls that support remote operations.

After all, there’s nothing suspicious about a process reading from or writing to its own memory.

We would basically change this:

With this:

CreateRemoteThread Limitations

The first problem we encountered with CreateRemoteThread was its parameter limitation. The API accepts only a pointer to the start routine (the code to execute) and a single pointer to its first argument.

While one parameter is enough for simple APIs like LoadLibrary, calling more useful functions becomes difficult. For example, VirtualAlloc and WriteProcessMemory both require four parameters.

Another issue is that any additional parameters (beyond the first) are not guaranteed to be NULL—they’re often just undefined garbage data. For instance, if you call MessageBox, you will get a message box in the remote process, but the title (2nd param) and text (3rd param) will likely be junk.

For our targets, we needed full control over all four parameters. Luckily, there’s a straightforward method to achieve this, which also acts as an execution trigger: Hijacking Thread Context.

By using APIs such as SetThreadContext, we can configure a target thread in the remote process to run VirtualAlloc and WriteProcessMemory with up to four controlled parameters.

With this limitation bypassed, we’re now free to call runtime functions like malloc, memset, memcpy, and also system-native functions such as RtlFillMemory, HeapAlloc and more.

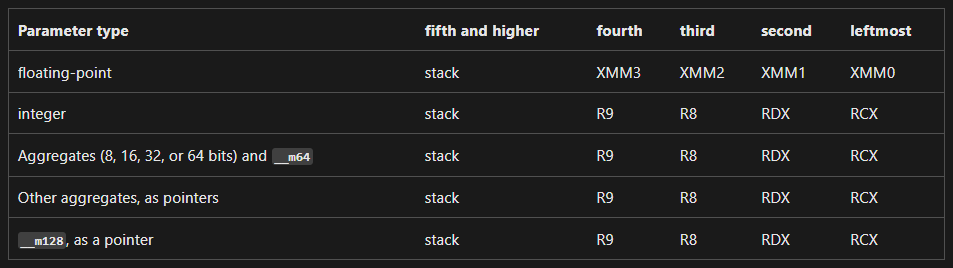

Before we continue to exactly how, let’s do a quick refresher on the x64 calling convention and how it relates to the CONTEXT struct which we use extensively.

Windows x64 Calling Convention 101

The x64 calling convention passes the first four arguments to a function via registers (RCX, RDX, R8, R9), and the remaining arguments are passed on the stack.

Practically speaking: If we can control the CONTEXT of a thread, we can set the RIP (instruction pointer) to any function we want to execute, and set up the registers to pass the appropriate arguments to that function.

For our second injection proof-of-concept, we aimed to adapt the classic Thread Hijacking technique: SuspendThread → SetThreadContext → ResumeThread — but apply it to a newly created thread.

Our intended flow looked like this:CreateRemoteThread (Suspended) → SetThreadContext → ResumeThread

This approach turned out to be challenging. However, we successfully worked around the issues while sticking to our rule: never use standard remote memory allocation or modification.

Troubleshooting & Research

This section is about the problems we’ve encountered and how we overcame those, it gets a bit technical and perhaps heavy, but we wanted to share our methodology.

Show Sections

Issue – Empty Initial Stack

Setup

First we’ve tried creating a new thread in a suspended state. Then we overwrite its CONTEXT struct so that when we resume the thread, it jumps right into VirtualAlloc.

RIP = &pVirtualAlloc

RCX = param1

RDX = param2

R8 = param3

R9 = param4

Result

We get a memory access violation crash on the return from VirtualAlloc.

Root cause

- The thread starts with an empty stack.

VirtualAllocexecutes fine and returns to its caller, but the caller’s return address is zero. That is because the return address is normally pushed to the stack by the thread‑startup stub, which did not happen.- Dereferencing the null return address triggers the memory access violation.

Why CreateRemoteThread doesn’t crash in 1‑arg cases

- When you let Windows launch a thread normally, execution begins in the

native startup stub (RtlUserThreadStart→BaseThreadInitThunk). - The stub sets up a proper stack frame, calls your target routine, then

finishes withExitThread. - However, when you forcibly set RIP to a function such as

VirtualAlloc, the thread starts inside the function and seems to skip the native startup stub. This means the thread can’t go toExitThreadonce it’s done.

Trial 2 – Stealing Valid Stack from Another Thread

Idea

Reuse the stack of a “sacrificial” thread that is sleeping forever using SleepEx (NtDelayExecution). The hope is that the call stack of the sacrificial sleep thread would be clean and safe to return through.

If the thread had been paused mid-call, say during stack setup (after the prologue but before the epilogue), we might need to realign the stack manually, e.g., adjusting RSP += 16 to compensate.

Plan

- Spawn sacrificial thread

CreateRemoteThread( hProc, NULL, 0, Sleep, (LPVOID)INFINITE, 0, NULL);

- Wait until the thread is inside

NtDelayExecution. - Grab its stack pointer

CONTEXT ctx;GetThreadContext(hSleep, &ctx);uintptr_t sleepRsp = ctx.Rsp;

- Create a second thread (suspended) and overwrite its

CONTEXT:

RIP = &VirtualAlloc

RSP = sleepRsp // borrow stack from the sleeping thread

RCX, RDX, R8, R9 = args // first four params

- Resume the second thread.

Outcome

- Crash on return to the native startup stub.

- Reason: the borrowed stack is valid, but the new thread’s TEB is empty.

BaseThreadInitThunkexpects initialized fields (SEH list, TLS, etc.).- Dereferencing

TEB → NtTib.ExceptionList(still NULL) triggers a memory access violation.

Lesson

A good stack alone isn’t enough. Each thread gets a fresh Thread Environment Block (TEB), and the kernel points the GS register to it. Returning into code that assumes those TEB fields are initialized will fail.

Our next idea was to hijack the sleeping thread itself instead of repurposing its stack.

Trial 3 – Hijacking the Sacrificial Sleep Thread

Goal

Hijack execution of a thread with a fully‑initialized TEB and stack after it enters SleepEx.

Intended call‑stack

RtlUserThreadStart

↳ BaseThreadInitThunk

↳ Sleep → SleepEx → NtDelayExecution

↳ (context switch) → VirtualAlloc

Steps

- Launch a sleeper thread for 1 second:

HANDLE hT = CreateRemoteThread( hProc, NULL, 0, Sleep, (LPVOID)1000, 0, NULL);

- Wait until

RIPsits insideNtDelayExecution. - Hijack context while the thread is still sleeping:

RIP = &VirtualAllocRCX,RDX,R8,R9 = desired parametersRSP left unchanged

- Let the timer expire; the thread should resume directly in

VirtualAlloc.

Outcome

RIPchanged as expected — execution reachedVirtualAlloc.- All other registers were junk;

VirtualAllocfailed and the process crashed on return.

Take‑away: during a timed sleep, only RIP is reliably written. The kernel’s wait‑resume path seems to overwrite or ignore the rest of the supplied context.

Where we pivot next

A cleaner target is a thread that is running yet idle – not blocked in a kernel wait but is post initialization.

That insight leads to Trial 4, where we start the thread in a minimal endless‑loop gadget that is trivial to hijack.

Trial 4 – Sleep alternative, the Loop Gadget and CFG

Idea

Start the thread in a busy‑wait loop (JMP -2) that touches no registers, then hijack its context.

Why the EB FE gadget?

- It’s a two‑byte “

jmp ‑2” instruction — an infinite loop. - Easy to locate in any executable module; we simply scan our own

ntdllfor it and reuse the same address in the target process. - Leaves every register except RIP untouched, so no collateral damage.

Expected call‑stack

RtlUserThreadStart

↳ BaseThreadInitThunk

↳ [loop gadget: EB FE]

↳ (context hijack) → VirtualAlloc

Procedure

- Create a remote thread whose start address is the loop gadget.

- Wait until it spins inside the loop.

- SetThreadContext

RIP = &VirtualAllocRCX,RDX,R8,R9 = paramsRSP unchanged

- Thread executes our function (no suspend/resume needed; the thread is already running).

Result

- Immediate Control‑Flow Guard (CFG) violation → process crash.

- Root cause:

BaseThreadInitThunkdispatches to the start address via an indirect jump that is CFG‑instrumented.

Our loop gadget wasn’t in the module’s valid call‑target bitmap, so CFG killed the thread before the loop even began.

Trial 5 – Double Hijack: Loop Gadget Pivot

Idea

Start with a normal thread startup into Sleep (to satisfy CFG), just like before. But this time, we hijack twice:

- First into a loop gadget, to gain stable execution control.

- Then into the target function (e.g.,

VirtualAlloc) with full parameter control.

Previously, we tried replacing the sleep function with a gadget directly — but that skipped the thread’s natural startup logic. We still wanted the native thread initialization to happen first, then slide quietly into a dormant state until hijack time.

The breakthrough was combining the two ideas:

- Let the thread start normally with

Sleep. - When it hits

NtDelayExecution, hijack it to a loop gadget. - From the loop, hijack again, this time fully setting the context (

RIP+RCX,RDX,R8,R9).

Call Flow

RtlUserThreadStart

↳ BaseThreadInitThunk

↳ ...

↳ NtDelayExecution (from Sleep)

↳ Context Hijack → Loop Gadget

↳ Context Hijack → VirtualAlloc (with params)

Execution Flow

CreateRemoteThreadwith start address set toSleep.- Wait briefly for the thread to initialize and enter sleep.

- Hijack #1: Set

RIPto the loop gadget. Leave everything else alone. No suspend/resume needed. - Hijack #2: Set

RIPtoVirtualAlloc, with proper values inRCX,RDX,R8, andR9. Again, no suspend/resume required.

Outcome

Success. We now have a clean PoC that calls any local function in a remote thread with up to 4 parameters, without using any standard remote allocation or modification techniques.

This approach even plays nicely with APC delivery, since the thread returns normally, without being sacrificed. The only downside? Two waits are needed per invocation to let the thread reach its sleep, and then the loop gadget.

Maybe we can optimize it a little if we could find an alternative to the initialization + sleep stage.

Trial 6 – Fixing the Stack using ROP

Idea

Finally, we thought of a simpler solution: use a ROP gadget in the target process to sets up the stack with two return addresses – one for thread exit (RtlExitThread) and one for our target function. This single gadget, would suffice for our stack building purposes.

Back in Trial 1, we ran into a problem: after the target function finished executing, the thread tried to return to a null address — a result of starting with an empty stack. We wanted more elegant ways to deal with this.

Waiting for thread initialization, sleeping, and doing two context hijacks (as in Trial 5) worked — but it felt a bit heavy-handed.

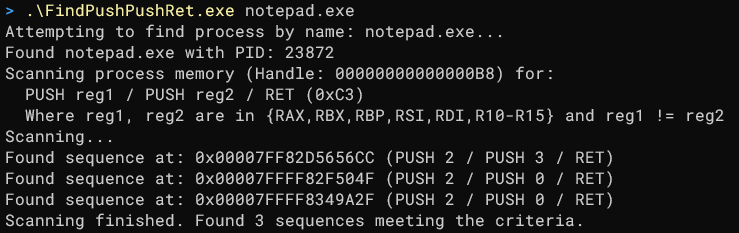

ROP Gadget

By using a ROP gadget already present in the target process, we could build a valid stack with just a single step.

The ROP gadget looks like this:

push reg1

push reg2

retWhere the two above registers are unique from one another, and are any of the following: RAX/RBX/RBP/RDI/RSI/R10-15.

With this simple gadget we can provide any API with following Context struct:

RIP→ Gadget addressRCX, RDX, R8, R9→ 4 arguments- Gadget register 1 →

RtlExitThread - Gadget register 2 → Pointer to Function (ex,

VirtualAlloc)

This way, we have managed to skip the initialization + sleep and create a clean stack which exits via RtlExitThread once the target function finishes its work.

Call Flow

ROP Gadget

↳ VirtualAlloc

↳ RtlExitThread

- We scan the remote process‘ memory for the desired ROP gadget.

- We create a new thread via CreateRemoteThread, in a suspended state. The thread’s start address is irrelevant.

- We prepare a new context:

- Set

RIPto the ROP gadget. - Set the gadget’s input registers to:

VirtualAlloc(function call target)RtlExitThread(post-call return target).

- Fill

RCX,RDX,R8, andR9with the fourVirtualAllocparameters.

- Set

- We resume the thread and let it run.

Outcome

The thread successfully executes VirtualAlloc and then cleanly exits by returning into RtlExitThread—no crashes, no cleanup needed.

Proof of Concept

The proof of concept performs the following:

- Searches the target process memory for a ROP gadget (

push reg1; push reg2; ret) - Uses this gadget to call

VirtualAlloc,RtlFillMemory, and execute shellcode- Creates a suspended thread using

CreateRemoteThread - Sets the thread’s

CONTEXTwithSetThreadContext, assigning:RIPto the ROP gadgetRCX–R9to function arguments- Stack values for

ExitThreadand the target function toreg1andreg2 - Calls

ResumeThreadto run the thread. - Each thread pushes the address of

ExitThread, then the target function, and performs aretto jump into the target function.

- Creates a suspended thread using

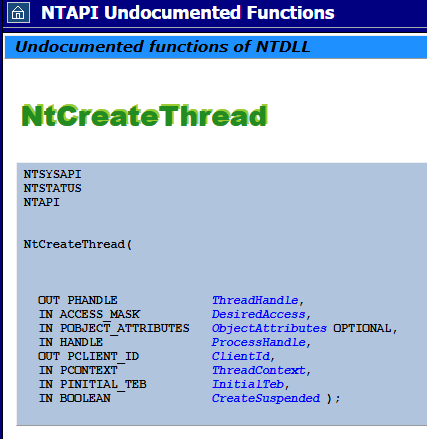

NtCreateThread Context Injection

While CreateRemoteThread is widely used for thread injection, it only accepts:

- The start address of the thread

- A pointer to the first argument.

This led us to wonder why it’s so limited, and what would happen if we investigated the underlying API (NtCreateThread) which provides more control over thread creation.

Post Research Note: This is a good moment to say – we thought that

CreateRemoteThreadcallsNtCreateThreadwhileCreateRemoteThreadExcallsNtCreateThreadEx.That is not true. In modern Windows, both APIs call

NtCreateThreadExwhich does not take a context struct as an argument. WithNtCreateThreadEx, the kernel performs stack allocation in the remote process.With

NtCreateThread, we can pass aCONTEXTstructure, giving us control over the thread’s registers, stack, and the return address.

This sparked an idea: what if we avoid using SetContext APIs by supplying the CONTEXT structure to NtCreateThread?

Troubleshooting & Research

At first, what seemed like it would be a walk in the park, turned into a few nights worth of debugging. This section gets a bit debugging heavy as well, but again, we wanted to share the methodology and our conclusions. Feel free to skip ahead.

Show Sections

NTSTATUS 0xC0000022 – Access Denied

Our first PoC was simple (or so we thought):

- Obtain

PROCESS_ALL_ACCESShandle to target process. - Get the

Sleep()function address from our process. - Allocate a clean stack using

VirtualAllocExto the remote process (we can likely can avoid this step by being a bit creative and combining previous ideas) - Prepare

CONTEXTStruct &TEBstruct in our process. - Call

NtCreateThread

However, we received an ‘Access Denied‘ NTSTATUS from the Syscall, even though we:

- Used a high integrity injecting process with an admin token and

SeDebugPrivilegeenabled. - Injected into medium integrity processes –

notepad.exe,calc.exe,msedge.exeand a dummy process we’ve created.

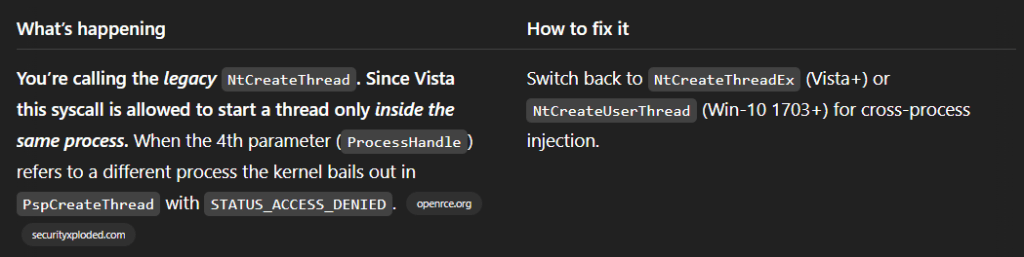

Looking in the internet, we didn’t find much info on the reason this happens, but ChatGPT gladly told us that the NtCreateThread syscall is a legacy syscall that will not work when used cross-process after Windows Vista:

That obviously seemed like a hallucination, especially when the sources GPT pointed to didn’t contain that wording explicitly, so we went ahead and did some kernel debugging.

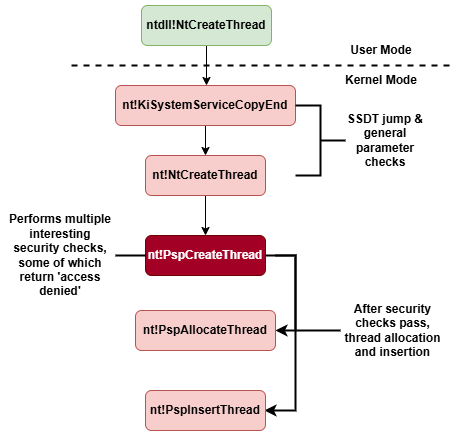

Tracing NtCreateThread in the Kernel

The general flow of the NtCreateThread syscall is:

Checks nt!NtCreateThread Performs

Before the kernel gets to nt!PspCreateThread, the nt!NtCreateThread wrapper does some basic housekeeping which include:

- Verifies all pointers passed in (handles,

CLIENT_ID,CONTEXT,INITIAL_TEB) are aligned and readable/writable. - Scrubs the

CONTEXTrecord, stripping out privileged flags and illegal register values. - Sanity-checks the stack info in

INITIAL_TEB, making sure a real stack was allocated and no “previous stack” fields are set. - Zeros the output handle & keeps the stack 16-byte aligned so any early error unwinds cleanly.

These are mostly safety checks, they’re not relevant to our troubleshooting but we thought to mention them.

Checks nt!PspCreateThread Performs

PspCreateThread is where the actual thread object (ETHREAD) is created and linked into the target process. It performs its own set of checks, some of which are more security-focused.

The PspCreateThead is lacking on documentation, so we’ve tried our best reversing it. The prototype is as follows (when called from NtCreateThread):

NTSTATUS __fastcall PspCreateThread(

PHANDLE RemoteThreadHandle,

ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes,

HANDLE RemoteProcessHandle,

_EPROCESS *TargetProcObject,

__int64 __zero,

PCLIENT_ID ClientID,

PCONTEXT InitialContext,

PINITIAL_TEB InitialTeb,

ULONG CreationFlagsRaw,

ULONG_PTR IsSecureProcess,

ULONG_PTR Spare,

PVOID InternalFlags)

First we have some initializations and caching of parameters:

callerThread = KeGetCurrentThread();

RemoteProcessHandle2 = RemoteProcessHandle;

RemoteThreadHandle2 = RemoteThreadHandle;

__zero_3 = __zero;

ClientID2 = ClientID;

InitialTeb2 = InitialTeb;

DesiredAccess2 = DesiredAccess;

callerProcess = (_EPROCESS *)callerThread->ApcState.Process;

InternalFlags2 = InternalFlags;

ObjectAttributes2 = ObjectAttributes;

CallerProcess2 = callerProcess;

Skip a bit forward, first, the kernel resolves the target process:

if ( RemoteProcessHandle )

{

LOBYTE(RemoteProcessHandle) = PreviousMode;

result = ObpReferenceObjectByHandleWithTag(

RemoteProcessHandle2,

2LL,

PsProcessType,

RemoteProcessHandle,

0x72437350,

&TargetProcessObject,

0LL,

0LL);

TargetProcessObject2 = (_EPROCESS *)TargetProcessObject;

goto LABEL_5;

}

Afterwards, the kernel checks that resolving the target process was successful and jumps to perform a check using PspIsProcessReadyForRemoteThread:

CallerProcess3 = CallerProcess2;

if ( TargetProcessObject2 != CallerProcess2 )

{

if ( !PspIsProcessReadyForRemoteThread(TargetProcessObject2) )

return 0xC0000001; // STATUS_UNSUCCESSFUL

CallerProcess3 = CallerProcess2;

}

Now things start to get a bit weird. There is a check to see if the target process is protected by virtualization and lives in VTL-1 (Secure Kernel), but since NtCreateThread always calls PspCreateThread with IsSecureProcess = 0, the check is skipped and is evaluated to True as part of the other conditions we can see just below.

We reach the key check that caused the Access Denied error:

if ( !__zero_3 // Always true from NtCreateThread

&& !IsSecureProcess // Always true

&& ((TargetProcessObject2->MitigationFlags & 1) != 0

|| (CallerProcess3->MitigationFlags & 1) != 0

|| (TargetProcessObject2->MitigationFlags2 & 0x4000) != 0

|| (CallerProcess3->MitigationFlags2 & 0x4000) != 0) )

{

return 0xC0000022;

}

The first two conditions evaluate to true when called from NtCreateThread. The next two checks (MitigationFlags & 1) determine whether Control Flow Guard (CFG) is enabled in either our process or the target. The final two checks (MitigationFlags2 & 0x4000) verify whether the Import Address Filter (IAF) mitigation is enabled on either processes.

Just a bit later there’s a few other interesting checks which could return 0x22:

if ( (TargetProcessObject2->Flags3 & 1) != 0 // Minimal Process bit

&& !TargetProcessObject2->PicoContext // Not a Pico Process

&& InitialContext )

{

return 0xC0000022;

}

The first condition checks whether the target process is a Minimal Process. and that is not a Pico Process and an InitialContext was provided (which it is from NtCreateThread.

To sum up, if any of the following applies to the target process, NtCreateThread injection will fail:

- Control Flow Guard is enabled

- Import Address Filtering (EAF) is enabled

- The process is a Minimal Process and not a Pico process.

Therefore, the NtCreateThread syscall will likely work on most 3rd party programs, which are typically not compiled with CFG or IAF, and are typcially not Minimal processes. In contrast, most Microsoft binaries are typcially compiled with Control Flow Guard (CFG).

Proof of Concept

The proof of concept performs the following:

- Searches the target process memory for a ROP gadget (

push reg1; push reg2; ret) - Uses this gadget to call

VirtualAlloc,RtlFillMemory, and execute shellcode- Allocate an empty stack in the target process for the new thread using

VirtualAllocEx(we can likely avoid this step) - Initialize

CONTEXTstruct, assigning:RIPto the ROP gadgetRCX–R9to function arguments- Stack values for

ExitThreadand the target function toreg1andreg2 - Each thread pushes the address of

ExitThread, then the target function, and performs aretto jump into the target function.

- Creates a thread using

NtCreateThreadwith the givenCONTEXTwhich executes immediately.

- Allocate an empty stack in the target process for the new thread using

The new thread does not need a context hijack while belonging to the target process as its context is already pre-supplied.

RedirectThread Tool

Find the RedirectThread Github repo here

To demonstrate the techniques from this blog in a practical and repeatable way, we built a command-line tool that implements the injection methods discussed. RedirectThread supports context-only process injections which include:

- Pointer-only DLL injection

- Various APC injections

CreateRemoteThread+SetThreadContextinjectionNtCreateThread

Usage:

Usage: C:\RedirectThread.exe [options]

Required Options:

--pid <pid> Target process ID to inject into

--inject-dll Perform DLL injection (hardcoded to "0.dll")

--inject-shellcode <file> Perform shellcode injection from file

--inject-shellcode-bytes <hex> Perform shellcode injection from hex string (e.g. 9090c3)

Delivery Method Options:

--method <method> Specify code execution method

CreateRemoteThread Default, creates a remote thread

NtCreateThread Uses NtCreateThread (less traceable)

QueueUserAPC Uses QueueUserAPC (requires --tid)

QueueUserAPC2 Uses QueueUserAPC2 (requires --tid)

NtQueueApcThread Uses NtQueueApcThread (requires --tid)

NtQueueApcThreadEx Uses NtQueueApcThreadEx (requires --tid)

NtQueueApcThreadEx2 Uses NtQueueApcThreadEx2 (requires --tid)

Context Method Options:

--context-method <method> Specify context manipulation method

rop-gadget Default, uses ROP gadget technique

two-step Uses a two-step thread hijacking approach

Additional Options:

--tid <tid> Target thread ID (required for APC methods)

--alloc-size <size> Memory allocation size in bytes (default: 4096)

--alloc-perm <hex> Memory protection flags in hex (default: 0x40)

--alloc-address <hex> Specify base address for allocation (hex, optional)

--use-suspend Use thread suspension for increased reliability

--verbose Enable verbose output

--enter-debug Pause execution at key points for debugger attachment

Example:

C:\RedirectThread.exe --pid 1234 --inject-dll mydll.dll

C:\RedirectThread.exe --pid 1234 --inject-shellcode payload.bin --verbose

C:\RedirectThread.exe --pid 1234 --inject-shellcode payload.bin --method NtCreateThread

C:\RedirectThread.exe --pid 1234 --inject-shellcode-bytes 9090c3 --method QueueUserAPC --tid 5678

C:\RedirectThread.exe --pid 1234 --inject-shellcode-bytes $bytes --context-method two-step --method NtQueueUserApcThreadEx2 --tid 5678

Injection Detection Logic Theory

This section is about detection logic models commonly used in EDRs, and how execution-only techniques challenge their core assumptions.

1. “Thread‑Context Hijacking” by itself isn’t evil

- A lone execution trigger. For example: suspending a thread, tweaking its

CONTEXT, and resuming it doesn’t touch memory and therefore looks benign. - Modern EDRs typically label process injection when two or more of the following activities are tied together in the same victim process:

| Activity | Typical API evidence | What it really means |

|---|---|---|

| Remote allocation | VirtualAllocEx, MapViewOfFile3, etc. | Create fresh pages inside another process |

| Remote modification | WriteProcessMemory, VirtualProtectEx | Change bytes or permissions in those pages |

| Remote execution trigger | CreateRemoteThread, APC queueing, context hijack, UI‑callback registration | Force the target to jump to attacker‑controlled code |

EDRs often model these as an ordered chain (1 → 2 → 3) or as any {2 of 3} combination.

This check is often done as a correlation check with the start address of a new Thread or APC, or on the event of an any API call involved in the activity.

2. Why Execution‑Only Attacks Are Hard to See

A defended endpoint would have to:

- Spot Trigger #1 (remote thread creation) – easy.

- Spot Trigger #2 (context hijack) – also easy.

- Elevate every subsequent local memory touch inside that thread to “remote”.

- Requires tracing all syscalls and user‑mode helpers (

memset, etc.). - Needs data‑flow (“taint”) analysis to prove the write originated from the foreign context.

- Impractical at scale; borderline impossible in real time.

- Requires tracing all syscalls and user‑mode helpers (

Result: attackers who skip Activities 1 & 2 and rely only on creative triggers could slip past detection.

3. Why Attackers Swap Triggers More Than Allocators

- The pool of “allocate/write remotely” APIs is tiny and heavily monitored.

- The execution surface is huge: threads, APCs, timers, UI callbacks, UMS, DCOM marshaling, and so on. It’s a fertile ground for variants.

- As EDRs hardened around memory ops, merely choosing an exotic trigger no longer guarantees stealth, yet it remains the easier and cheaper option.

4. Weakness in the 2 of 3 Philosophy

The model silently assumes “remote ≠ local”. Once an attacker coerces the victim into performing its own writes, that assumption fails:

- Local write occurs (

memsetinside victim). - Write is actually driven by an external context hijack = logically remote.

- Current telemetry can’t prove that causal link, which results in no alert.

Unless the defender can join trigger telemetry with deep intra‑thread taint tracking, the injection hides in plain sight.

5. Takeaways for Defenders

For what we’ve discussed in the blog:

- Monitoring for rapid set of thread creation events in a short amount of time might prove useful.

- Monitoring thread creation followed by a large number of

SetThreadContext(and similar APIs).

But the above detections are API specific, to get to the bottom of things we’d need to correlate who requested the trigger, not just what API was called.

Research Notes

This is a section for things we did not pursue, unanswered questions and other details.

Are we limited to 4 arguments?

No. The Windows x64 calling convention gives us four registers (RCX, RDX, R8, R9) for arguments, but if needed, additional arguments could be placed on the stack manually if we find better ROP chains.

Can we avoid creating hundreds of threads?

Probably yeah. We explored reusing the same thread by re-hijacking its context multiple times.

Instead of pushing RtlExitThread, we could push a loop gadget (as discussed in the troubleshooting section here and recycle the thread.

This could reduce thread creation in cases where you want to perform multiple operations over time, especially for shellcode delivery.

We could potentially hijack existing waiting-to-run threads in the right state such as DeferredReady/Ready waiting to run and restore their state later. This could also be done using the gadget by pushing the previous address instead of an exit. This would achieve a similar result to the earlier two-step approach with APCs, but with the efficiency of the later approach.

Can we avoid ReadProcessMemory to find ROP gadgets?

Yes! While our approach was to search directly in memory, this certainly isn’t the only viable method. There are several potential alternatives which can work:

- Option 1: Load the same DLLs used by the target process and scan them locally to find ROP gadgets within specific modules.

- Option 2: Parse the PE file from disk, locate the gadget, then calculate its memory address using

base address + offset.

Each method has trade-offs in precision, stealth, and complexity. We chose in-memory scanning mainly for its simplicity.

Can we use other WinAPI / NT functions to control the Context?

The answer is yes! While not all of APIs are suitable for cross process injection, some just might offer a bit of ‘stealthier’ way to achieve the same results.

The following is a non-definitive list of APIs we’ve found that accept a CONTEXT struct. However, not all of them were tested, as the list quickly grew too large to completely explore.

- WinAPI:

SetThreadContextSetThreadInformationWow64SetThreadContextRtlWow64SetThreadContextRtlRestoreContextRtlRegisterFeatureConfigurationChangeNotificationRtlRegisterWaitSetUmsThreadInformationEtwRegisterUpdateProcThreadAttributeUmsThreadUserContext

- NT Functions:

NtSetContextThreadNtCreateThreadNtSetInformationThreadThreadWow64ContextThreadCreateStateChangeThreadApplyStateChange

NtContinueNtContinueExALLOCATE_VIRTUAL_MEMORY_EX_CALLBACKEtwEventRegister

Optimizations?

Absolutely! plenty of optimizations could be made:

We could improve gadget discovery logic by:

- Tolerate non-disruptive intermediate instructions (e.g., a gadget like

push rax; push rbx; mov r10, r11; ret, wheremov r10, r11has no side effects). - Look for other instructions. Eg.

push rax; call rbx;. - Use chains instead of a monolith. Use one gadget to prepare rsp, a second to save registers, a third to dispatch. ROP.

We could improve two-step approach’ efficiency by:

- Using more than a single thread at a time, automating thread’s choice too. The writing/copying operation can be done for each byte in parallel.

- Shortening the sleep timing, looking for better ways to detect when thread is ready for the next step.

- Using the

Nt*versions for the writing operation. As they support 3 parameters (perfect fitRtlFillMemory) we can skip the two-step hijack for the majority of the operation.

Unexplored Ideas

| Idea | Conclusions |

|---|---|

| Catch the thread before it returns, suspend it, and reuse it | Not explored. Seemed impractical due to tight timing. We didn’t investigate delaying the thread’s exit in a reliable way. |

Find a native function that accepts a callback (e.g., to redirect to ExitThread) | We brainstormed a trampoline approach to redirect the call chain to an exit, but couldn’t find a good native candidate in NTDLL/Kernel32/KernelBase. |

| Push an existing exit function already present on another thread’s stack | Not explored. In theory, wait until a thread calls ExitThread, then reuse the stack pointer. But it’s a narrow and volatile time window, and likely dangerous. |

| Find an exit function address already present in memory | We scanned for common function pointers (like ExitThread, RtlExitUserThread) but didn’t find usable results. This sub-idea remains unresolved. |

| Catch exceptions during bad returns via debug APIs | Not explored. Likely violates the “no extra process hooks” principle of this research. Could be interesting in separate work. |

| Inject a custom SEH (structured exception handler) | Theoretically interesting. We wondered whether an execution-only setup could install a handler without modifying memory. Left untested. |

A Note on “GhostWriting” and Related Work

When we kicked off this project we could find no public write-ups that fully skipped both VirtualAlloc[Ex]/WriteProcessMemory and still delivered x64 code. Only after nearing the end of our research did we stumble on the GhostWriting research [1] [2] [3], which is incredible.

GhostWriting proposed the idea to steal an existing thread and manipulate its CONTEXT to run shellcode with no remote allocations. Our research started from the same intuition but diverged in three ways:

- Pointer-only

LoadLibraryinjection. We show that feedingLoadLibraryAa pointer to an in-process ASCII literal (e.g.,"0") plus a disk file named0.dllachieves DLL loading with zero remote writes. GhostWriting focuses solely on raw shellcode. - CreateRemoteThread ➜ SetThreadContext ROP pivot. Instead of hijacking a live GUI thread, we spin up new remote threads, repair their empty stacks with a

push reg; push reg; retgadget, and chain any WinAPI with up to four params. This workflow doesn’t appear in prior papers (as far as we know and happy to be corrected). - Full x64

NtCreateThreadPoC. Our demo supplies a craftedCONTEXTandINITIAL_TEBdirectly toNtCreateThread, along with a kernel-debug exploration of the CFG/IAF gates.

So while “execution-only” injection has history, we believe the variants, mitigations, and insights presented here push the idea into a new territory.

Conclusion

If you made it this far, you’ve earned a debugger coffee breakpoint, hope it was worth the stack space.

Thanks for reading, sticking through the details, and joining us down this rabbit hole. If you’ve got follow-up ideas or ways to push this further, we’d love to hear them, someone out there always finds the next clever step.